Indigenous Literature in the Philippines: Traditions and Transformations

The Filipino’s earliest ancestors traveled to the Islands from other points of Asia and Southeast Asia. They migrated by land or by sea on boats known today as barangay. They settled in caves and in time dispersed to other places in the archipelago, settling in villages lining the coasts of bays and seas, the shores of lakes, or the banks of rivers near sources of food and livelihood. They also settled in mountains and valleys all over the archipelago.

The Aeta were the first to arrive, about 30,000 years ago. They lived in the lowland coastal areas until successive migration wars with the Malay drove them farther and farther inland and into the mountains. Over the centuries, the Malay groups took over the different parts of the archipelago and became known as the Ivatan in Batanes; the Tinguian, Ibaloy, Kankanaey, Bontok, Kalinga, and Isneg of the Cordilleras; the Gaddang, Isinay, Itawes, Ibanag, and Ilonggo in the Caraballo and adjacent areas; the Mangyan of Mindoro; the Tagbanwa of Palawan; the Tausug, Samal, Sama Dilaut, Yakan, and Jama Mapun of the Sulu areas; the Maguindanaon, Maranao, Manobo, Bagobo, Bukidnon, Tboli, Subanon, and other related groups in Mindanao; and the largest groups of all: the Ilocano, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Tagalog, Bikol, Cebuano, Waray, and Ilonggo. The Maguindanaon, Maranao, Tausug, and other Mindanao groups were Islamized in the late 14th century, as were the Tagalog. The advent of Spanish colonization, however, resulted in the Christianization of the Tagalog together with the Ilocano, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Bikol, and the Visayan groups.

The literary tradition among indigenous Philippine groups was mostly oral. A problem, therefore, arises when one attempts to study the samples of this oral literature, especially before the 16th century, since the recording of this literature was done by the Spanish colonizers only from 1521 to the 19th century. Among those who described or gave samples of the early poems, narratives, and songs were Antonio Pigafetta, 1521; Miguel de Loarca, 1582; the author or authors of the Boxer Codex, circa 1590; Pedro Chirino, 1604; Francisco Colin, 1663; and Francisco Alcina, 1668.

During the Spanish period, grammarian-philologists recorded some poems and songs to illustrate the usage of words. Among the works with literary texts are Father Gaspar de San Agustin’s Compendio del Arte de la Lengua Tagala (A Compendium of the Grammar of the Tagalog Language), 1703; Father Francisco Bencuchillo’s Arte Poetica Tagala (The Art of Tagalog Poetry), written ca 1775 and published in 1895; Father Juan de Noceda and Father Pedro de Sanlucar’s Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (Vocabulary of the Tagalog Language), 1754 and 1869; and Father Joaquin de Coria’s Nueva Gramatica Tagalog Teoretica-Practica (New Theoretical-Practical Tagalog Grammar), 1872. These and many others written in other Philippine languages like Kapampangan, Cebuano, and Ilocano had the additional merit of recording for posterity the traditional poetics. For example, Father Alonso de Mentrida’s Arte de la Lengua Bisaya-Hiligayna de la Isla de Panay (Grammar of the Bisaya-Hiligaynon Language of the Island of Panay), 1618 and 1894, contains a “Lista de Varios Refranes” (List of Various Proverbs) and a treatise on poesia Bisaya or Visayan poetry (Manuel 1986, 387-401).

Through more than three centuries of Spain’s colonization and four decades of American rule, many European and American literary forms introduced into the country were adopted and adapted by native writers, especially by those who were educated in Westernized schools. The arrival of these Western forms, however, did not necessarily lead to the obliteration of indigenous literature. That the ethnic literary traditions were able to withstand the cultural impositions of the colonizers can be attributed to two factors: geographic inaccessibility and the native resistance to colonial domination (Lumbera and Lumbera 1997, 3), as in the case of ethnic groups in the Cordillera of northern Luzon and in the mountains and remote islands of Mindanao. The wisdom and learning of elders continue to be passed down orally through the generations, reflecting the people’s reaction to changing realities of society under foreign domination.

Today, these indigenous forms continue to live not only among those cultural communities hardly touched by Westernization, but even among lowland Christian Filipinos, especially those in rural communities. In these colonized communities, the ethnic traditions become assimilated in the mainstream culture, asserting their steady presence even in residual forms.

As documented by Spanish chroniclers and philologists from 1521 to 1898, American anthropologists from 1901 to the present, and Filipino anthropologists and literary scholars in the past century, ethnic literature created by the ordinary folk in the oral tradition may be classed into folk speech, folk songs, epics, and folk narratives.

Folk Speech

The shortest forms of folk literature, called folk speech, consist of riddles, proverbs, and short poems. Known as bugtong in Tagalog and Kapampangan, tigmo in Cebuano, burburti in Ilocano, tugma in Ilonggo, kabbuñi in Ivatan, tukudtukud in Tausug, and paktakon in Hiligaynon, the riddle is a traditional expression using one or more images that refer to an object that has to be guessed. Riddles flex one’s wits, sharpening one’s perception and capacity to recognize similarities and contrasts. They are also occasions for humor and entertainment. Images from nature or from the material culture of the community may be used as metaphor or the object to be guessed. Riddles may come in one, two, three, or four lines. There is no set meter although there is palpable rhythm. Rhyme tends to be assonantal.

|

| A riddle from Daniel Palma Tayona’s Bugtong, Bugtong 2: More Filipino Riddles, 2013 (Tahanan Books for Young Readers) |

|

| A riddle from Daniel Palma Tayona’s Bugtong, Bugtong 2: More Filipino Riddles, 2013 (Tahanan Books for Young Readers) |

|

| A riddle from Daniel Palma Tayona’s Bugtong, Bugtong 2: More Filipino Riddles, 2013 (Tahanan Books for Young Readers) |

This Subanon riddle (Eugenio 1982, 419) sensitizes listeners to the natural world around them:

Kayo sa Canoojong,

bagyohon dili mapalong. (Aninipot)

(The fire of Burawen

can never be put out by hurricane. [Firefly])

This Cebuano tigmo sharpens the wit by confronting the listener with a paradox:

Han bata pa nagbabado,

Han bagas na, naghuhubo. (Kawayan)

(Dressed when young,

Naked when old. [Bamboo])

Riddles also serve as vehicles for the expression of political sentiment. This Karay-a paktakon of Antique evinces an anticolonial attitude with its reference to the greed of friars (Puedan 1988, 254):

Nagtanum ako sing granada

Sa tunga sang amon lagwerta

Pito ang puno, pito ang bunga

Madamu nga pari namupo sang bunga. (Pitong Sakramento)

(I planted a pomegranate

In the middle of our field

Seven trees grew, each with seven fruits

Many priests picked all the fruit. [Seven Sacraments])

This Butbut af-af-fok alludes to the intrusion of military forces in the indigenous communities of Cordillera (Lua 1994, 172):

Affom:

Anna toro pulo wenno

Afat a pulo a sorchacho

Wa ummoy cha maarafan

Ad Kordilyera

No mansubili cha ket

Lamang cha mangangitit. (Sagkay)

(Guess what it is:

There were thirty to forty soldiers

Who went to fight in the Cordillera

When they came back,

They were all black. [Comb])

A proverb expresses the norms and strictures of the society and conveys general views on human life. Known as salawikain in Tagalog, kasabian in Kapampangan, sanglitanan in Cebuano, pagsasao in Ilocano, hurubaton in Ilonggo, pananahan in Ivatan, and masaalla in Tausug, it uses a metaphor derived from nature or daily life, this time to refer not to an object but to a truth that can apply to different situations in life. In form it is similar to the riddle. This Ilocano pagsasao underscores the importance of vigilance, using an image familiar to fisherfolk:

Iyanud tidanunti

Matmaturog nga udang.

(Water carries away

the sleeping shrimp.)

This Kapampangan diparan warns that what looks soft and easy is what binds together (Hilario-Lacson 1984, 21):

Ing silung malambut

Matalik ya igut.

(A soft lasso

Has a tight pull.)

This Bikol sasabihon points out that one who is afraid will never achieve anything (Galdon 1980, 166):

An matakot sa doron

Daing aanihon.

(One who is afraid of locusts

Will never harvest anything.)

An example of the short poetic form is the Tagalog tanaga. This is a heptasyllabic quatrain or a stanza of four lines with seven syllables per line. It uses a talinghaga (metaphor) derived from a person’s environment to express human experience. While this poetic form could possibly be traced back to the precolonial period, the earliest known examples are those that were gathered in Vocabulario de la Lengua Tagala (Vocabulary of the Tagalog Language), 1754 and 1869, by the Spanish friars Juan de Noceda and Pedro de Sanlucar. As such, these may already have been influenced by Spanish colonialism. This Tagalog tanaga illustrates the folly of excessive ambition with the talinghaga of a hill trying to be a mountain:

Mataas man ang bondoc

mantay man sa bacouor

iyamang mapagtaloctoc,

sa pantay rin aanod.

(Though the hill be high

and reach up to the highland,

being desirous of heights,

it will finally be reduced to flat land.)

Modern writers have created various incarnations of the tanaga in dealing with present-day concerns. An example is this tanaga about the hollowness of crass materialism (Panganiban 1963, 19):

Alahas, gara, yaman

Dangal, kapangyarihan,

Madlang ari-arian

Kulang pa rin, at kulang.

(Jewelry, grandeur, wealth,

prestige, power

Immense property,

Not enough, still not enough.)

In an effort to rekindle interest in the tanaga through technology, the Likhaan: University of the Philippines Institute of Creative Writing, in cooperation with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, launched the “Textanaga” in 2003. This is a poetry competition in which participants send their tanaga entries via text messaging.

A longer form of folk speech is the extemporaneous debate, known as dallot or arikenken in Ilocano; duplo in Tagalog; tigsikan, kangsin, or abatayo in Bikol; and balitao in Cebuano and Aklanon. The debate may be a flirtatious banter between a man and a woman, or a toast. Verbal jousts test the people’s talent for spontaneous versification, as well as strengthen the bond of the community in times of merriment and grief. They take place during wakes, as in the case of the duplo, or during drinking sprees, as in the case of the tigsikan. The indigenous verbal jousts persisted throughout the colonial period and served as precursors to later forms of poetic duel like the balagtasan of the Tagalog and the bucanegan of the Ilocano.

|

| Duplo, a contest of wit in verse between men and women assembled in a funeral wake (CCP Collection) |

In this excerpt from a Cebuano balitao, the woman challenges the amorous young man’s declarations (Alburo et al 1988, 36-37):

LUIS: Kanang sudlay mong sisik

Sa buhok nagatugabong

Ingon sa gugmang naglabtik

Sa dughan nagapanghagbong

PINAY: Kining sudlay kong sisik

Timaan kini sa katarong

Nga sa sulting palabtik

Dili kini palimbong

(LUIS: That comb of tortoise shell

Atop the bundle of your hair

Is as love that taunts me still

And makes my breast pound.

PINAY: This comb of tortoise

Stands for righteousness

That words that tease

Will not see me teased.)

Folk Songs

Songs created by the folk may be divided into the lyric or situational, which emphasizes expression of thought or emotion, and the narrative, which tells a sequence of events. Songs are chanted solo, chorally, or antiphonally, in the home or in large feasts at the village circle. The song is called awit in Tagalog, Kapampangan, and Cebuano. Folk songs are usually classified according to their function in the everyday lives of the people. Examples are songs for nature, the lullabies, songs of love and courtship, wedding songs, dirges for the dead, and the occasional songs for working and drinking.

Folk songs may document the people’s actual historical experience. This excerpt from a Subanon song sung by Rapinanding Promon refers to the danger posed by the presence of outsiders (Aleo et al. 2002, 4-5):

Sabang Tebed, mibengkal.

Dumeguk, mipalesu

Dumelinaw, mipenglaw.

Pelanduk, guminindaw.

Lumegem, pilebu’an.

Lubetis, pinugya’an.

Kabesalan, mitutung.

Si’ay, misindapug.

(At the mouth of the Tubod, banks collapsed and fell.

The River Dumagoc was left in disarray.

The Dumalinao River became a lonely stream.

Palandok River asked where all had gone.

Lumugom was humbled by a frightful plague.

Lobatis suffered unutterable shame.

Kabasalan burned to the ground,

Reduced to ashes too was Si-ay town.)

The lullaby puts infants to sleep with its languid tunes and repetitive lyrics. Most lullabies are whimsical and fanciful, but some are serious and didactic, like this Tagalog uyayi (Eugenio 1982, 430-31):

Kung lumaki’t magkaisip

ikaw bunso’y magbabait

mag-aaral na masakit

ng kabanalang malinis.

(When you grow up

be good, my child

persevere in learning

to be clean and

holy.)

Love between man and woman occasioned exquisite poetry, but friar-philologists of the time were averse to propagating it. Hence, little of it is available in friar records. It is from recordings of 20th-century ethnography that sample texts of surviving traditions were obtained. The ambahan of the Hanunoo Mangyan of the Mindoro islands is an exchange of verses chanted by a man and a woman to each other, as illustrated by this excerpt (Postma 1972, 51-55):

|

| Ambahan chanting and inscription with Gawad sa Manlilikha ng Bayan awardee, Ginaw Bilog, right, circa 1993 (CCP Collection) |

Salod anong bugtungan

Kis-ab kang mag-iginan

Ginan kang tipit lingban

Bunggo madi uyunan

Kang di tinalisigan

Kang bay nga pagsumayan

Padi man ga bungguan

Una sa unay kagnan

Una babaw aghuman

Kang ka-abay sag lan-gan

Ka-ugbay sag ranukan.

(My sweetheart, my love so dear,

when I left, in coming here,

coming from my house and yard,

all the rice that I have stored,

I have left it there behind,

because I hope here to find

one more valued than my rice!

One to be my partner, nice

to the water, to the field,

a companion in my trips,

and one who will share my sleep.)

But the girl is prudent and would wish to know and test the lover more:

Umraw anong awayan

Saysay mamaukaynan

Mama-ukayno duyan

Sarin ka pag mangginan

Mangidungon aw kaywan

Mamaybay aw banasan

No sis indungon kaywan

Ya ngap urog nga ginan

Sinya singko da-uyan

Ha panulos tarn lan-gan

Halaw sis pangulinan.

(My dear boy, as bamboo straight,

may I ask you something now,

just one question I will say:

tell me, please, where are you from?

Are you from the mountain slopes

or do you live at the shore?

If the mountains are your home,

well, that is to me, all right.

You are welcome in this place.

But if you are going home,

you had better leave me here!)

The Mangyan also compose ambahan to depict contemporary issues plaguing their community. This example expresses the anguish brought about by displacement and foreign intrusion (Nono and Aves 1998, 18-19):

ko nag-ayan od ya

sa akong mga kakilala

ugma ako’y may mga kasama

halin sa ibang bansa

pa iwan kami diya

kami kung makauli

odto sa among isla

kami mga tagaMindorinya

Mindorinya

kami nga tanan

mga katutubo sa una

ad yos ka luba si pangdan

(I have come to your place

To be among friends

I am a Mangyan

From Mindoro Oriental

How shall we fare, we are still here

I do not know if we can still return

We will be going back to our village

We are from Mindoro

We have been part of the land from the very beginning

We were here before any

Foreigner came.)

Using a sharp iron blade on a bamboo node or a flat bamboo strip, the poet chants as he etches the ambahan words, or lyrics, in the old Hanunoo Mangyan script.

The practice of pamaeayi (dowry negotiations) is highlighted in this song sung by an Ati househelp (dela Cruz 1958, 20-21):

Kuti-kuti sa Bhandi,

Bukon inyo baray ray,

Rugto ro inyo sa pang-pang;

Dingdingan sing pirak,

Atupan sang burawan.

Burawan, pinya-pinya

Gamut sang sampaliya,

Sampaliya, marunggay,

Gamut sang gaway-gaway,

Gaway-gaway, marugtog,

Gamut sang niyog-niyog,

Busrugi ko’t sambirog.

Tuman kung ika busog,

(Stir the drums of Bhandi,

That is no longer your old home,

Over there is yours by the river.

With walls of shining silver

And roof of beaten gold;

The gold of ripe pineapple

Becomes the root of bitter melon.

Sampaliya, marunggay

Becomes the trunk of the gaway-gaway,

Gaway-gaway, marugtog

Is the root of niyog-niyog;

Just drop down one young coconut for me

It’s enough to keep me full.)

Wedding songs among the Christianized groups reveal Spanish influence. In this example, the bride-to-be pays her respects to her parents before she embarks on an uncertain fate in her married life (Eugenio 1982, 452-53):

Adyos Nanay, adyos Tatay

Tapos na ang inyong pagbantay

Mana-ug ko sa hinay hinay

Mangita ko ug laing Nanay.

Makabana gani’g maayo

Maayo sab akong pagbantay

Makabana ug abobhoan

Adlaw gabii hibokbokan.

(Goodbye, Mother; goodbye, Father

Your responsibilities are over

I will go down very slowly

To find a new mother.

If I marry a good man

My life will be well taken care of

If I marry a jealous man

Then day and night I’ll be beaten.)

The Ilonggo song “Dandansoy” is a farewell song of someone who is about to leave. As such, it may be said to represent the life of the sakada (seasonal cane worker), who leaves his home province of Antique for the sugarlands of Negros, or the seafarers of Iloilo. Here is an excerpt (Villareal 1997, 88-89):

Dandansoy bayaan ta ikaw

Mauli ako sa payaw

Ugaling kon ikaw hidlawon

Ang Payaw imo lang lantawon

Dandansoy nga akon pagmahal

Dandansoy ginhatag sa iban.

Gugma ko para sa imo lang

Gugma nga waay sang katapusan.

Dandansoy kon bilog ang bulan

Pirme ka nga madumdoman

Kag didto sa langit nga matahom

Kaupod ka sang mga bituon

Kasingkasing ko nga ginamingaw

Nagaantos kay wala man ikaw

Ang mga adlaw nga nagligad

Kabudlay akon ginabatyag

(Dandansoy I will leave you

I will return to Payaw

But in case you long for me

Just gaze at the Payaw

Dandansoy why has my love

Dandansoy been given to another

My love is for you only

Love that is without end.

Dandansoy when the moon is full

It’s you I always think of

And up there in the beautiful sky

You are with the stars

My heart that is so lonely

That suffers because you are not here

In the passing days

Misery is what I feel.)

Collective work is more efficiently done when accompanied by song. The community work song among the Ivatan is the kalusan, which they sing while clearing their farms or rowing their boats. Driving the rowers to pull hard together, they sing (Hornedo 1979, 345):

Un as kayaluhen, kakaluhen

Un si payawari, parinin,

Un nu akma diwiyaten.

Un as payawa, paypisahen;

Un as payawa, palangen,

Un si wayayat mo nay.

(Yes, let us hurry, let us hurry then.

Yes, we pull the oars with rhythm, so let it be.

Yes, let it be by rowers like us.

Yes, we pull the oars with rhythm, for once let it be.

Yes, we pull the oars with rhythm, let us pull.)

|

| Kalusan, sung by the Ivatan when rowing boats, such as above (CCP Collection) |

This Tagalog awit describes the difficulties of a fisher’s life (Eugenio 1982, 453):

Ang mangingisda’t anong hirap

Maghulog bumatak ng lambat

Laging basa ng tubig dagat

Pagal at puyat magdamag.

(The fisherfolk’s life is so hard

To cast the net and pull it back,

Always wet with sea water,

Tired and sleepless the whole night.)

Often the folk get together for a few rounds of drinks to relax. These are their occasions for singing and making merry. An example of a drinking song is this tagay from Cebu (Eugenio 1982, 459):

Ay, Liding, Liding, Liding,

Ay, Liding, Liding, Liding,

Uhaw tagay.

Uhaw tagay.

Kon walay sumsuman,

Ihawan ang hinuktan.

Uhaw tagay

Uhaw tagay.

(Ay, Liding, Liding, Liding,

Ay, Liding, Liding, Liding,

I am thirsty; let us drink.

I am thirsty; let us drink.

If there is no sumsuman

Kill the hinuktan

I am thirsty; let us drink.

I am thirsty; let us drink.)

In a Bukidnon sala (lyrical poem), “Pandalawit ta Had’I pa Ag-inum” (Prayer before Drinking), the singer pays respect to his ancestors. This excerpt warns against the danger of drunkenness (Unabia 1996, 194-97):

Yan bayà ku lalag

Sa dayambà ulinan a

Pinted hu managlendem

Biday bansalanan a

Na bà kan su babat-awan

Hu kandilà ha kamanyan

Sulù ha Salumayag

Iman ku ihampang a

Iatubang ad iman

Ku dadayungdung ku hindang

Na iyan nu manugindan

Taglilibauntang sa yugbu

Ta salikaw ha’gsayasaya en

Ku baganbang hu inumen.

(This is what my mind wants

Like a ship, I be unguided

Whatever is in my mind I desire

Like a sea vessel, I be unguided

I who am enlightened

by the candle kamangyan

In the torch of Salumayag

And now in my search

For those who face

The jar covered by hindang leaf

This will surprise you

Because they are both in need

And are afraid that is why they forbade

Drunkenness by liquor.)

Songs have always been part of the tribal rituals for the dead. When a person dies, the community holds extended funerals, at which poems of lamentation, such as the Ilocano dung-aw, and the narrative of the dead person’s life are chanted for several nights. This dirge from Sagada is sung during the wake when the body in state is tied to the sangadil or death chair (Eugenio 1982, 165-68):

Id cano sangasangadom,

wada’s inan-Talangey ay bayaw ay nasakit,

ay isnan nadnenadney

San bebsat inan-Talangey, maid egay dda iyey

Bayaw issan masakit, ay si inan-Talangey

Sa’t ikikidana dapay anocan nakingey

Wada pay omanono ay daet obpay matey.

San Nakwas ay nadiko, ay ba’w si inan-Talangey

Dadaet isangadil, issan san tetey

Da’t san ab-abiik na napika et ay omey

Bayawan ay manateng ab’abiik di natey

Aydaet

mailokoy si’n anito’y sinkaweywey

Nan danen daet mattao bayaw ya mabaginey.

(A long time ago, it is said, there was Inan Talangey

Who had been sick for a long time

The brothers and sisters of Inan Talangey,

they did not bring

To the sick who was Inan Talangey

But she was lying in bed and yet was very fussy

And at length she finally died.

After she died, she Inan Talangey

They tied her to the death chair near the ladder

Then her soul started to go

To join the souls of the dead

She went with a long line of anitos

Their path was grassy and among the mabaginey.)

Ballads and Epics

Narrative songs and chants are the ballads and the epics. Ballads narrate particular episodes or events, whereas the epic is an expansive narrative composed of a series of episodes recounting the many exploits of one hero or a set of heroes.

The poetic narrative of the Parang Sabil of Sulu narrates the heroic self-immolation of Muslims who wished to die as witnesses to their faith and enter Paradise riding a white stallion. Outstanding among these narratives is the Tausug Parang Sabil of Abdulla and Puti Isara in Spanish Times.

Similar to the Parang Sabil are ballads or folk hero stories in chanted poetry from the Amburayan-Bakun river valleys on the western sub-Cordillera in the Ilocos inland, like the Allusan, the Da Delnagen ken Annusan Lumawig (Delnagen and Annusan Lumawig), and the legend of Indayuan on the founding of the town of Sugpon by the Amburayan River between Ilocos Sur and La Union in northwestern Luzon.

Called a sarita (story), the Indayuan, which comes from an inland culture called Bag-o, is sung in the musical chant style called baguyos, which is used for singing hero stories. The story purports to be about the lovely Indayuan, but it eventually gets caught up in the history of an exodus of groups of refugees.

Toward the end, the story tells about how Sugpon got its name, with the accent shifted to the cooperation and mutual help or sugpon, through which the town was founded. Although it does not unfold chronologically, the story nevertheless is clearly about the flight of a people from oppression in order to find a better way of life, free according to their own fashion.

The duyuy nga traki (narrative chants) of the Dulangan Manobo tell of the experiences and interactions of the community with their world. A traki narrates how the world began when Nemula beckoned the first man, Tug Fu Tao, to expand the coin-sized land that stood amid the watery world. Another traki recounts the arrival of the Milkano (Americans). The Americans brought with them medicine, but it could not rival the power of Manobo medicine at healing diseases (Cruz-Lucero 2007, 182, 203).

The Hiligaynon composo is a shorter ballad, usually about an actual event either of historical significance or with a melodramatic content. An example is the Kumposo sang Natabo Marso 29 (Composo about the Incident on March 29), which recounts the abduction of eight locals by military elements during the martial law period (Cruz-Lucero 2001, 450-51)

Religious ballads include the Visayan daygon and Waray panarit, which narrate various episodes of the birth of Christ, including the adoration of the Magi, and the Tagalog pangangaluluwa, which tells of a beggar (Christ in disguise) asking for shelter for a night and leaving money with the kind host.

The ethnoepics are the longest narrative poems of the Philippines. E. Arsenio Manuel (1963, 3) defines them as narratives of sustained length, based on oral tradition, revolving around supernatural events or heroic deeds, and embodying or validating the beliefs, customs, ideals, or life values of an ethnic group. The epic heroes are depicted as possessing extraordinary physical and supernatural powers.

The epic wields a pervasive influence on the religious, political, and social aspects of the daily life of the people. Its presence in the complex dynamics of ethnic life is evident in various permutations: in tribal musical performances, in proverbs and supplications, in narrative chants and songs, in religious rituals, and in folk drama (Mojares 1983, 18).

The various local terms for epic mean song/singing or chant/chanting, like the dalagangan, the Ifugao hudhud, the Subanon guman, the Maguindanao and Maranao darangen, the Mansaka diawot, and the Manobo owaging, ulaging, ulahingon, or ulahingan.

Among the many epics now in print in their original texts and in translation are the Ullalim of the Kalinga, the Hudhud of the Ifugao, the Lam-ang of the Ilocano, the Nanang: I Taguwasi anna i Innawagan of the Agta, Ibalong of the Bikol, the Labaw Donggon of the Panayanon Sulod, the Kudaman of the Palaw’an, the Darangen of the Maranao, the Raja of Madaya of the Maguindanao, the Agyu of the Ilianon and the Bukidnon, the Ulahingan of the Livunganen-Arumanen, the Tuwaang of the Manobo, the Sandayo and the Keboklagan of the Subanon, the Berinareu of the Teduray, and the Maharadia Lawana of the Maranao.

|

| The Maguindanao Raja of Madaya, 1984 (University of San Carlos) |

One of the most famous epics is the Ilocano Biag ni Lam-ang (Life of Lam-ang), which relates the adventures of the hero Lam-ang. Endowed with supernatural strength and the gift of speech even at birth, he avenges his father’s death by defeating the culprit Igorot in a spectacular battle. He falls in love with the beautiful Ines and after many ordeals marries her in a ceremony of unmatched splendor. During a rite of passage in which he has to catch the rarang fish, he gets swallowed by the berkakan fish, but is soon magically brought back to life (Foronda 1978, 4). Documented in writing during the Spanish period, the epic shows Spanish influences in the names of characters, objects, and customs mentioned.

The Ifugao Hudhud is chanted during important social festivities, like the harvest and weeding seasons, marriage feasts, or the wake of an important community leader. The hudhud has many versions, all centering on the exploits of the hero Aliguyon. He seeks the enemy of his ancestors to earn more glory for himself, his comrades, and his tribe. All versions mirror the simple, unadorned life of these mountain people and affirm the theme of self-preservation and continuity of the tribe. Always these epics legitimize tribal customs and the power of the leaders.

The Kalinga Ullalim Banna relates the adventures of the hero Banna. Sent by his parents to court the maiden Laggunawa, he faces the daunting task of slaying the giant Kumaw. He is soon rescued by Gallawi of Kabbasila and marries one of his daughters, Gassinu. Years later, upon learning of the marriage, Laggunawa confronts Banna and Gassinu. The epic closes with murder and a vow of peace (Constantino 2002).

From the Labin Agta Negritos of Cagayan comes the Nanang: I Taguwasi anna i Innawagan, the first known Negrito epic to be recorded and published. It recounts the abduction of the maiden Innawagan to be married off to the sky god Kalimangalnuk. When her brothers all fail to defeat the god, she enlisted the help of the warrior Taguwasi. After episodes of fierce battles, Taguwasi succeeds in freeing Innawagan who eventually becomes his wife (Constantino 2001).

The Ibalong, the epic-fragment of the Bikol, which was first recorded during the Spanish colonial period, recounts the great feats of the three heroes in the land of Ibalong. The hero Baltog kills the monstrous wild boar that plagued the land. Handyong defeats several monsters and together with his men, establishes settlement in the land. Soon, Ibalong faces destruction from natural calamities and a half-man half-beast monster called Rabot appears. The third hero Bantong defeats the monster and restores peace to the land (Espinas 1996).

From Panay island comes the Hinilawod, of which a part called Labaw Donggon has a printed version consisting of 2,325 lines. The epic is an account of the adventures of the hero Labaw Donggon, a handsome semidivine being. First he courts and marries Ginbitinan; soon after the wedding, he falls in love with Anggoy Doronoon of the underworld and marries her. Not long after, he again desires another woman, Malitung Yawa Sinagmaling Diwata, who lives where the sun rises. She is the wife of Saragnayan, who is in charge of the course of the sun. After his sons defeat Saragnayan, Labaw Donggon finally wins over Malitung Yawa, and he promises to love his three wives equally (Jocano 1965).L_HE_Indigenous_5

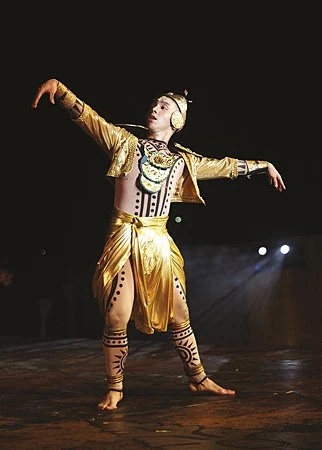

|

| Gio Gahol as the titular character in Ateneo ENTABLADO’s Labaw Donggon: Ang Banog ng Sanlibutan, 2013 (Ateneo ENTABLADO) |

Another portion of this epic relates the adventures of Humadapnon. He embarks on a journey to find the powerful maiden Labaw Donggon whom he wants to be his wife. Accompanied by his magically conjured brother Dumalapdap, the hero has to face great tribulations in the enchanted island of Tarangban, where well-kept maidens called binukot seduce him. Eventually, with the help of Labaw Donggon, he is able to break free from their enchantments and return home (Jocano 2000).

The Olaging of the Bukidnon is about the Battle of Nalandangan and the invincible hero Agyu. It is the story of a people’s pride in their homeland, which they share with divinities, and their great kaamulan or merrymaking festivals in which they celebrate themselves and their heroes, the greatest of whom is Agyu. Despite casualties, they win the battle. Another great merrymaking takes place, a celebration so glorious that even Agyu’s dead father returns as a ghost to be part of the celebration. A female hero is Matabagka, Agyu’s sister. She successfully fends off forces about to invade Nalandangan, their fortress, at a time when it is most vulnerable because the men have gone off on a sea expedition.

|

| Volume Five of the Maranao Darangen, published in 1988 (Mindanao State University) |

The Darangen of Maranao recounts the great feats of the Islamic people. Among the story cycles is the narrative of the hero Bantugan as he defends his kingdom and embarks on expeditions for wealth, love, and friendships. The Darangen cycle also contains contemporary elements, thus affirming the enduring presence of the epic in the lives of the Maranao. For example, government soldiers intrude into the communities at the behest of the American colonizers (Labi 2009, 161-80).

Another Maranao epic, Maharadia Lawana, recounts the adventures of two royal brothers, Mangandiri and Mangawarna, who vie for the hand of the beautiful Tuwan Potre. After Mangandiri wins the sipa (kickball) contest, the brothers are tasked to kill the giant snake before the betrothal is formalized. Thereafter, the brothers battle the many-headed Maharadia Lawana who has abducted Tuwan Potre. After defeating the abductor, the princes return home with the maiden and are welcomed with a celebration (Francisco 1969).

|

| Sining Kambayoka’s Laksamana, 2013, a dance-drama taken from the Maranao epic Maharadia Lawana, performed in Prambanan, Indonesia (Sining Kambayoka Ensemble) |

The Berinareu of the Tiruray centers on the hero Lagei Lengkuos, aka Seonomon, a belian (shaman), as he tries to save the abducted Seangkaien, his future spouse. However, she discovers that Seonomon has been betrothed to another lady, Linauan Kadeg. Enraged, she wages war against Seonomon and is victorious. The two are about to reconcile when a curse that she has earlier pronounced on Seonomon causes his death. Seangkaien revives Seonomon and the two reunite (Wein 1989).

The Tboli epic Tudbulul centers on the hero Tudbulul, who is miraculously conceived by his already aged parents, Kemokul and Lenkonul. The boy who displays immense strength at an early age has a premonition that he would die of drowning. He thus embarks on a series of adventures before returning to his town of Lemlunay. The town is swallowed by the sea, fulfilling the premonition. Eventually, Tudbulul comes back to life, marries Solok Minum, and carries out his destiny as defender of his homeland (Buhisan 1996).

|

| The Bikol Ibalong, 1996 (University of Santo Tomas Publishing House) |

These epics continue to inspire writers. Hudhud, for example, has had a number of literary incarnations, among which is Virgilio Almario’s epic poem Huling Hudhud ng Sanlibong Pagbabalik at Paglimot para sa Filipinas Kong Mahal (Last Hudhud of a Thousand Returns and a Forgettings of My Beloved Philippines), 2009, which recounts Aliguyon’s encounters with different Filipino literary and historical figures. The epic-fragment Ibalong has inspired Abdon Balde’s Ang Awit ni Kadunung (The Song of Kadunung), 2008, which traces the adventures of a scholar named Peter, who returns to Bicolandia to embark on the heroic quest of rediscovering the forgotten fragments of the region’s epics.

The indigenous epic narratives have also established their presence in modern literary forms. For instance, the komiks hero Kulafu, who first appeared in the pages of Tagalog magazine Liwayway in 1933, embodies the heroic types that hail from the epic narratives (Reyes 2009, 395-97). During the 1970s, komiks adaptation of epic narratives appeared. Among the titles were Prinsipe Bantugan, 1974; Lam-ang, 1974; and Indarapatra at Sulayman, 1981 (Reilly 2013, 226).

Folk Narratives

The narratives created by the folk are stories told in prose. Called alamat or kuwentong bayan in Tagalog, alamat in Kapampangan, kasugiran in Cebuano, sarita in Ilocano, gintunaan or sugilanon in Ilonggo, kabbata or istorya in Ivatan, and kissa in Tausug, folk narratives are handed down by word of mouth through the generations. They include myths, legends, folktales, and numskull tales.

Myths are narratives believed by the societies that created them to be true accounts of events that happened in ancient times. They are used to explain the way things are in the world. They accompany ritual and are thus considered sacred. Generally, myths are of two spheres: one inhabited by visible beings and the other by invisible beings, who are more powerful than the former. To mediate between these two worlds, the mediums known as the babaylan in Visayas and the catalonan among Tagalogs, who have special gifts, read the messages of the gods from omens and intercede for the people for forgiveness and blessings. Occasionally, these spiritual leaders propitiate them with offerings or exorcise them.

One of the myths still popular among the Tagalog and Visayan is about the origin of the Islands. According to this myth, there was a big conflict between the sea and the sky. The sea lashed at the sky with its waves, while the sky threw stones at the sea. The stones became the islands. The myth also speaks of the lawin (hawk) that pecked a bamboo tree, which broke open, revealing si babae, the first woman, and si lalaki, the first man.

A myth of creation found among the Subanon of Mindanao is that of the great god Diwata who had an only son, Demowata. Desiring to become independent, Demowata asked for a home of his own. Diwata took a piece of Heaven and created the earth. Then he drew a circle. Inside the circle was land, and outside was water. Demowata lived on land served by Balag, Diwata’s prime minister. The light in the sky, the chain of days and nights, and the creatures of the earth were made for love of Demowata. But he was lonely and needed friends, so Diwata took some clay and fashioned it after the image of his son. But sunlight dried it up and caused it to crack in two equal halves. Le and Lebon, the first man and woman, were born, equal in every way until Balag betrayed his master and seduced the humans. Having been reduced to an eel, Balag contrived to tempt the humans to approach the water, which they had been forbidden to touch. Le and Lebon, creatures of clay, were splashed with water, and their bodies swelled when they got wet. As evil crept into Langkonoyan, the earthly paradise, Diwata considered forgiveness, but not the restoration of original grace. He took his son back into the sky, leaving the humans to eke out a living for themselves on the cursed earth and to chew betel nut to remind them that life is bitter.

Myths have been reimagined in contemporary literary forms. In The Warrior Dance and Other Classic Philippine Sky Tales, 1998, Neni Sta. Romana Cruz retold eight myths for younger audiences. Among the myths are the Ifugao story of the first rainbow and the creation of Panay island. Rene O. Villanueva wrote children’s stories based on indigenous narratives like the Bagobo myth of Mebuyan who nourishes dead infants in the underworld (Villanueva 2005, 158-61). His version of the Panay myth “Tungkung Langit and Alunsina” won the Palanca award for children’s story in 1990.

Legends are stories about heroes and local tales of buried treasures, enchanters, fairies, ghosts, and saints. If myths are sacred, legends are secular. The events they recount are believed to have happened more recently than those in myths, and they are regarded as true by their traditional narrators. Legends may be etiological in purpose—that is, explanatory of how things came to be. These narratives are commonly populated with humans as principal characters, and are regarded as oral counterparts of written history. In some cases, legends also center on enchanted figures, saints, and ghosts. In the legends of mountain enchantresses Mariang Makiling of the Tagalog, Maria Sinukuan of the Kapampangan, and Maria Cacao of the Cebuano is traceable the historic memory of the race as it passed through the ages of grace as well as exploitation.

|

| Retelling of the legend of Maria Cacao by Rene O. Villanueva, 2002 (Lampara Books) |

The legend of Maria Makiling, popularized by Jose Rizal, is about a beautiful enchantress whose haunt is Mount Makiling in Laguna. She is not only beautiful; she is also a benefactress to the simple people who live near her mountain, rewarding the good and punishing the wicked. She falls in love with one of the young men there, but he is unfaithful and Maria disappears. With her vanish her blessings. The people are left in distress. In Rizal’s retelling, Mariang Makiling is spurned by the lover who chooses to live in colonial submission rather than to escape to the mountains. Ultimately, she herself becomes a victim of friar land-grabbing (Rizal 1962, 86-92).

In Mount Arayat in Pampanga resides another mountain enchantress, Mariang Sinukuan. Legend has it that she is courted by a man named Simeon. She agrees to accept his offer of love, but only if he successfully constructs a bridge that will connect her house to the church and if he finishes it before eight in the morning. Simeon agrees to the condition. When he is already on the verge of finishing the bridge at six, Maria causes the tolling of the church bells. Simeon halts the construction and accepts his defeat (“sumuko”). This explains Maria’s name, “Mariang Sinukuan,” Maria the unconquerable (Fansler, n.d., 3:1).

From Cebu comes the legend of Maria Cacao, a fairy who owns a vast cacao plantation. She lives in the cave of Lantoy on the mountain of Argao. When the moon is full, she appears to the townspeople. During her travels to America to sell her cacao nuts, she brings back new kitchen- and dinnerware. To borrow them, all the townspeople have to do is ask her at the mouth of her cave, and the utensils are delivered to their door the next day without fail.

Maria Cacao rides a golden ship in her travels. The ship is so tall, the bridge of Argao collapses every time she passes under it. The engineer tasked to rebuild and make the bridge higher begs Maria Cacao not to pass under it anymore. She agrees, the bridge is saved, but that is the last time she is seen. Because some people fail to return the things they borrow, she has stopped lending them anything. When other bridges in the area collapse, people say that Maria Cacao is probably passing under them (Alburo 1977, 39-40).

In some communities, the distinction between myths and legends is blurred. Among the Cordillera groups, legends often have mythical dimensions. One example is the Bontok legend of Lumawig and Kabigat, which explains the origin of the ritual called sibsib. Before leaving to hunt in the woods, the brothers Lumawig and Kabigat tell their father Boliwan to guard the deer meat at home. When they return, they find that the meat is gone. The brothers accuse their father of eating the meat. To prove his innocence, Boliwan slices his own abdomen and dies. A snake eventually admits to the theft. In order to appease the angry brothers, the snake, who is an anito (god), promises to heal their father’s wounds and bring him back to life. He puts rocks, stones, sticks and spears around the wound and starts praying. This becomes the ritual known as sibsib (Tolentino 2001, 19).

Reimaginations of legends have brought forth short story anthologies like Alternative Alamat, 2011, and the Philippine Speculative Fiction series, 2005-10, in addition to popular graphic novels also based on supernatural legends. Arnold Arre’s The Mythology Class, 1999, centers on an anthropology student whose encounter with a mysterious teacher leads her to the creatures of the underworld known only to her through her grandfather’s stories. The graphic novel series Trese, 2005-11, by Budjette Tan and KaJo Baldisimo, follows a female detective who investigates crimes of supernatural origins.

The legend of Mount Mayon arising from the grave of Daragang Magayon and Ulap inspired Bikolano writer Merlinda Bobis to write the epic poem Cantata of the Warrior Woman, Daragang Magayon, 1993, in which the maiden is reinvented as a warrior princess.

|

| Scene from Daragang Magayon: An Istorya ni Mayon, CCP, Manila, 2013 (Photo courtesy of Joey Salceda) |

The supernatural beings that populate Philippine legends are the subject of several literary retellings. Amando Osorio’s version, 1940, of the Maria Cacao legend reimagines the enchantress as a militant leader whose enchanted warships constantly blasts the stone bridge constructed during the Spanish colonial period through forced labor by the Spaniards. In the novel Ang Ginto sa Makiling (The Gold in Makiling), 1947, novelist Macario Pineda turns the legend of Mariang Makiling into an allegorical tale of social greed in postwar Philippines. Eugene Evasco retells the story of the Kapampangan mountain nymph for younger audiences in his storybook Mariang Sinukuan: Ang Diwatang Tagapag-ingat ng Bundok Arayat (Mariang Sinukuan: The Enchantress Guardian of Mount Arayat), 2006.

A great many folktales are extended humor narratives, recounted for amusement when folk gather together at the end of the day. Folktales include animal tales, fables, märchen, trickster tales, and numskull tales.

In animal tales, animals take on human qualities. They usually show how an animal outwits another animal through clever or deceptive tricks. A very ancient and well-known animal tale is “Ang Pagong at ang Matsing” (The Tortoise and the Monkey), made famous by Jose Rizal. A tortoise and a monkey plant halves of a banana tree. Thinking that the upper part with leaves would bear fruit soon, the greedy monkey plants the upper half. Naturally, it withers. The tortoise, on the other hand, gets the ugly-looking lower portion with the roots, but it flourishes and soon is laden with fruit. The tortoise, however, cannot climb the tree to gather the fruit, so the monkey volunteers to pick them. He eats all the bananas while he is up on the tree, throwing the skin down on the tortoise. Angry, the tortoise plants some shards of snail shells around the tree and hides under a coconut shell. The monkey comes down and lands on the shards. Wounded and bleeding, he searches for, and finds the tortoise. As punishment he gives the tortoise two choices: to be pounded with a mortar or be thrown into the water. The clever tortoise chooses the mortar and deceives the monkey into thinking that he is afraid of drowning. The monkey throws the tortoise in the water, where the latter soon surfaces laughing (Rizal 1962, 103-4).

Another example of an animal tale is the Tinguian “The Carabao and the Snail.” A carabao bathing in a river meets a snail and ridicules the snail for its slowness. The snail protests and challenges the carabao to a race. After running a long distance, the carabao stops and calls out, “Snail!” A snail lying by the river answers. After a long while, the carabao stops again and calls; another snail responds. The carabao, surprised that a snail could move so fast, runs on and on until he drops dead (Eugenio 1989, 31).

A fable is an animal tale that has a didactic function. The Cebuano tale titled “The Frog Who Wanted to Be as Big as an Ox” begins when two young frogs see their sibling crushed to death by the hoof of an ox. The frogs rush home to report the incident to their mother frog. The mother, believing that she can be as big as the ox she will fight, puffs herself up and asks her children if she has become as big as the ox. The children say no. No matter how much she puffs her self up, she still cannot equal the ox’s size. She keeps puffing until she bursts (Eugenio 1989, 82).

Some folktales are classified as märchen or tales “of some length involving a succession of motifs or episodes … [They happen] in an unreal world without definite locality or definite characters and are filled with the marvelous” (Eugenio 1982, 9). Most Philippine märchen are local adaptations of foreign folktales. A tale of tender beauty is the story of the swan maiden, of which 27 versions have been identified all over the country. One version from the Mansaka is about a man who takes a maiden as his wife by stealing and hiding her wings and feathers while she bathes in a lake. They have a child. One day while he is gone she finds her wings and flies away. He searches for her and recovers her only after much difficulty and after performing impossible tasks.

Tricksters are among the most popular characters in folk literature. These heroes use their wit and cunning to get the better of authority figures like the king and ferocious animals. The Visayan Pusong, the incorrigible prankster, victimizes plebeian and king without distinction. Condemned by the king to drown for playing a trick on him, Pusong is able to get a man to take his place by telling him that the king is forcing him to marry his beautiful daughter. The king, surprised to see Pusong alive, threatens to put him in prison, but Pusong is able to convince the king that the king’s dead parents and relatives would like him to visit them at the bottom of the sea. The king then decides to take Pusong’s place, so he has himself put in a cage and thrown into the sea. Pusong then becomes king.

Another trickster, Pilandok, regales the people of Mindanao with his outrageous pranks. Asked by Bombola why he is tied to a tree, he replies that the sky is going to fall and being tied will save him by forcing him not to panic. Bombola pleads to be saved too. Upon Pilandok’s orders, he unties Pilandok and gathers rattan from the forest to tie himself with. Bombola stays tied to the tree until he dies of hunger and thirst. Other remarkable tricksters are the Bikol Juan Usong, the Visayan Juan Pusong, and the Ilocano Guachinango.

|

| The perennial trickster Pilandok, featured in Ateneo ENTABLADO’s Si Pilandok at ang Bayan ng Bulawan, 2010 (Kevin C. Tatco) |

A numskull tale is a story depicting the stupidity of a nitwit like the Tagalog Juan Tamad. In the story “Juan and the Alimango,” Juan is asked by his mother to buy crabs and palayok (clay pots) in the market. Too lazy to carry the crabs, he makes them walk home, and to make it easier to carry the pots he makes a hole at the bottom of each, puts a string through the holes and carries them home strung together. In the end, Juan and his mother have no pots for cooking nor crabs for their meal.

The numskulls and tricksters have been interpreted as rebellious figures in folk narratives. As evinced by their Christian names, some of these characters emerged during the colonial period, and thus served as symbols of survival in the colonized society. By using wit or playing dumb, they successfully fooled authority figures whose presence ushered oppression and social inequality (Aguilar 2005, 95-97). For example, the Aklanon trickster Bonifacio “Payo” Bautista mocks and plays tricks on the gobernadorcillo or mayor (dela Cruz 1958, 40). Arriving from the lineage of local tricksters is the popular komiks hero Kenkoy, created by Antonio Velasquez, who, with his “carabao English” and flippant adoption of Western behavior, satirically depicts colonial mentality (Reyes 2009, 395-97).

Philippine folktales have survived time and change through various channels. Retelling folklore attended instruction during the early years of American occupation. Camilo Osias published Philippine Readers, 1920, a series of textbooks for elementary students which contained local myths, legends, and fables. The seven books in the series are the earliest readers containing folklore authored by a Filipino. Dean Fansler’s Filipino Popular Tales, 1921, was an anthology of folktales gathered by his students in the University of the Philippines. The first volume of Philippine Prose and Poetry, 1927, a literature series for secondary students, contained a section on folklore with four selections: an essay by H. Otley Beyer, an Ilocano folktale, a Bikol legend, and a Cebuano folktale (Eugenio 1987, 176-78).

The development of children’s literature in the Philippines has been driven by the commitment to instill among young Filipinos a profound sense of appreciation for the country’s literary tradition, and this has kept folktales alive. Writers like Maximo Ramos wrote Tales of Long Ago, 1953, and Philippine Myths and Tales, 1957. Manuel and Lyd Arguilla and I. V. Mallari retold folk narratives for young readers in Philippine Tales and Fables, 1957, and Tales from the Mountain Province, 1958, respectively.

|

| Book cover of folk tales published as children’s literature by Neni Sta. Romana-Cruz, published in 1993 (Tahanan Books for Young Readers) |

The effort continued in the 1990s and beyond, in books like Why the Piña Has a Hundred Eyes and Other Classic Philippine Folk Tales about Fruits, 1993, by Neni Sta. Romana Cruz. Sylvia Mendez-Ventura retold eight animal tales in the illustrated storybook The Carabao-Turtle Race and Other Classic Philippine Animal Folk Tales, 1993. Pilandok has been reincarnated in the Adarna Books’ Pilandok series, with titles like Si Pilandok at ang mga Buwaya (Pilandok and the Crocodiles), 1994; Si Pilandok at ang Manok na Nangingitlog ng Itlog (Pilandok and the Hen that Laid Golden Eggs), 1995; Si Pilandok: Ang Bantay ng Kalikasan (Pilandok: The Guardian of Nature), 1998; Si Pilandok sa Kaharian sa Dagat (Pilandok in the Kingdom under the Sea), 1998; and Si Pilandok sa Pulo ng mga Pawikan (Pilandok in Turtle Island), 2001.

|

| Book cover of folk tales published as children’s literature by Neni Sta. Romana-Cruz, published in 1993 (Tahanan Books for Young Readers) |

Publishing houses specializing in children’s literature have also spurred more publications that turn to folklore. Alemar-Phoenix, for instance, published collections of folklore for children like Philippine Folktales, 1969, by Gaudencio V. Aquino, Bonifacio N. Cristobal, and Delfin Fresnosa, and Myths and Legends of the Early Filipinos, 1971, by F. Landa Jocano (Parayno 1991, 19-20). Today, publishing houses for children’s books like Adarna House and Lampara Books continue to release titles and series derived from folktales, like Maria Cacao: Ang Diwata ng Cebu (Maria Cacao: The Enchantress of Cebu), 2002, and Si Pagong at si Matsing (Turtle and Monkey), 2006.

|

| Book cover of folk tales published as children’s literature by Sylvia Mendez Ventura, published in 1993 (Tahanan Books for Young Readers) |

Several folktales have been reincarnated in modern literary forms. During the 1920s, “Mga Kuwento ni Lola Basyang” (Stories of Grandma Basyang), introduced by Severino Reyes, appeared in the pages of the Liwayway magazine. The fictional grandmother has since then regaled several generations of Filipinos with her retellings of folktales in various platforms—radio, television, film, and theater. In the storybook "Mga Kuwento ni Lola Basyang", 2005, Christine Bellen retells some of Lola Basyang’s stories, such as the Cinderella-derivative “Ang Dalagang Bukid na Naging Prinsesa” (The Barrio Lass Who Became a Princess) and the legend of the mountain nymph “Maryang Makiling.”

|

| Ballet Manila’s Tatlong Kwento ni Lola Basyang, a ballet adaptation of selected stories from Severino Reyes’s popular anthology (Erica Jacinto) |

Folktales have also proved a veritable treasure trove for contemporary writers. Toward the end of the 1970s, Nick Joaquin’s children’s books, collectively called Pop Stories for Groovy Kids, use folk motifs, characters, and materials, including Maria Makiling and Juan Tamad. These are reimagined for an urban middle-class readership familiar with Western fairy tales (Gutierrez 2014).

In Joaquinesquerie: Myth a la Mod, 1983, which includes the stories published in the Pop Stories series, Joaquin transplants some fairytales into the local setting. For instance, “The Mystery Sleeper of Balete Drive” fuses “Sleeping Beauty” with the famous legend of the white lady believed to haunt drivers in Quezon City. Contemporary writer Bob Ong has fashioned a modern-day fable in his graphic novel Alamat ng Gubat (Legend of the Forest), 2003. The protagonist crab, Tong, searches for the banana heart to heal his father, the king, and encounters a host of animals entangled in a tug-of-war for power in the jungle that stands as an allegory for the Filipino society.

Continuing Tradition

Today, the ethnic tradition remains alive, surviving centuries of encounter with alien cultures, especially among the various cultural communities who experienced only the slightest intrusion from colonial powers. Even in heavily colonized territories, these indigenous forms have managed to brave the invasive proliferation of Western influences. In fact, no radical discontinuity can actually be spoken of between folk literature and contemporary literature.

The advent of colonial education did not obliterate indigenous literary traditions. As shown above, folk literature has become integrated in pedagogy, providing an opportunity for its preservation and proliferation.

The founding of publishing houses devoted to the publication of children’s literature further spurred vigorous literary productions derived from local folklore.

Scholarly endeavors on Philippine indigenous traditions continue today, as evidenced by the spur in the publication of documented oral literature from the regions courtesy of university presses and organizations like the Philippine Folklore Society and the Summer Institute of Linguistics. The development of technology in the Philippines has also presented more means of documenting local ethnic traditions. The performancce of the Darangen and Hudhud has been video-recorded and uploaded on the Internet via video-sharing websites like YouTube. Philippine Epics and Ballads Archive, which was launched in 2011, is a website that serves as an online repository of folk literature (Reilly 2013, 207). As important, writers continue to mine the ethnic tradition for their poetry, stories, and novels.

In the search for a Filipino national cultural identity, the importance of folklore cannot be overestimated. Oral literary tradition lies at the deepest layer of the national culture; it is the Filipino’s recourse in times of greatest joy and deepest sorrow, the spring from which flows the national consciousness.

Sources

- Aguilar, Mila D. 2005. “Fighting Panopticon: Filipino Tricksters as Active Agency against Oppressive Structures.” Philippine Humanities Review 8:84-109.

- Alburo, Erlinda K., ed. 1977. Cebuano Folktales. 2 vols. Cebu: San Carlos Publishing.

- Alburo, Erlinda K., Vicente Bandillo, Simeon Dumdum Jr, and Resil B. Mojares, eds. 1988. Cebuano Poetry / Sugboanong Balak until 1940. Cebu City: University of San Carlos Cebuano Studies Center.

- Aleo, Edgar, et al. 2002. A Voice from Many Rivers / Su Gesalan nu nga Subaanen di Melaun Tinubigan: Central Subanen Oral and Written Literature. Translated and annotated by Felicia Brichoux. Special monograph issue, Philippine Journal of Linguistics, no. 42. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

- Buhisan, Virginia. 1996. “Tudbulul: Ang Awit ng Matandang Lalaki.” PhD diss., University of the Philippines Diliman.

- Constantino, Ernesto, trans. and annot. 2001. Nanang: I Taguwasi anna i Innawagan: An Agta Negrito Epic Chanted by Baket Anag. Kyoto: Nakanishi Printing Company.

- ———, annot. and ed. 2002. Ullalim Banna: A Kalinga Epic, Inyullalim Gaano Laudi, iDalupa, Pasil, Kalinga, Pilipinas (Sung by Gaano Laudi from Dalupa, Pasil, Kalinga, Philippines). Kyoto: Nakanishi Printing Company.

- Cruz-Lucero, Rosario, ed. 2001. “Western Visayas Literature.” In Filipinos Writing: Philippine Literature from the Regions, ed. Bienvenido Lumbera, 425-80. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

- ———. 2007. Ang Bayan sa Labas ng Maynila / The Nation beyond Manila. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- De la Cruz, Beato. 1958. Contributions of the Aklan Mind to Philippine Literature. San Juan, Rizal: Kalantiao Press.

- Espinas, Merito B. 1996. The Ibalong: The Bikol Folk Epic-Fragment. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House.

- Eugenio, Damiana, ed. 1982. Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Folklore Studies Program and the University of the Philippines Folklorists Inc.

- ———. 1987. “Folklore in Philippine Schools.” Philippine Studies 35 (Second Quarter): 175-90.

- ———, ed. 1989. Philippine Folk Literature: The Folktales. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Folklore Studies Program and the University of the Philippines Folklorists Inc.

- Fansler, Dean, comp. n.d. “Finding List of Philippine Folklore (FLPF).” Typescript.

- Foronda, Marcelino. 1978. Dallang: An Introduction to Philippine Literature in Ilokano and Other Essays. Edited by Belinda A. Aquino. Honolulu: Philippine Studies Asian Studies Program, University of Hawaii.

- Francisco, Juan, annot. 1969. Maharadia Lawana. Quezon City.

- Galdon, Joseph, SJ, ed. 1980. Salimbibig: Philippine Vernacular Literature. Quezon City: Council for Living Traditions.

- Gutierrez, Anna Katrina. 2014. “Nick Joaquin and Groovy Kids: A Critique of His Stories for Children.” Perspectives in the Arts and Humanities Asia 4 (2): 1-18.

- Hilario-Lacson, Evangelina. 1984. Kapampangan Writing. Manila: National Historical Institute.

- Hornedo, Florentino H. 1979. “Laji: An Ivatan Folk Lyric Tradition.” Unitas 52 (Jun-Sep): 189-511.

- Ileto, Reynaldo. 1979. Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Jocano, F. Landa. 1965. The Epic of Labbaw Dongon. Quezon City: University of the Philippines.

- ———. 2000. Hinilawod: Adventures of Humadapnon (Tarangban 1). Metro Manila: PUNLAD Research House.

- Labi, Hadji Sarip Riwarung. 2009. “Dimakaling: Hero or Outlaw? A View from a Maranao Folk Song.” Journal of Sophia Asian Studies 27:161-80.

- Lua, Norma. 1994. “Butbut Riddles: Form and Function.” Philippine Studies 42 (Second Quarter): 155-76.

- Lumbera, Bienvenido L., 1986. Tagalog Poetry 1570-1898: Tradition and Influences in Its Development. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- ———. 2000. Writing the Nation / Pag-akda ng Bansa. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Lumbera, Bienvenido L., and Cynthia Nograles Lumbera. (1982) 1997. Philippine Literature: A History and Anthology. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

- Manuel, E. Arsenio. 1955. Dictionary of Philippine Biography. Vol. 1. Quezon City: Filipiniana Publications.

- ———. 1963. “A Survey of Philippine Epics.” Asian Folklore Studies 22:1-76.

- ———. 1970. Dictionary of Philippine Biography. Vol. 2. Quezon City: Filipiniana Publications.

- ———. 1986. Dictionary of Philippine Biography. Vol. 3. Quezon City: Filipiniana Publications.

- Mojares, Resil B. 1983. Origins and Rise of the Filipino Novel: A Generic Study of the Novel until 1940. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Nono, Grace, and Bob Aves. 1998. Marino: Hanunuo Mangyan Music and Chanted Poetry. Tao Music.

- Panganiban, Jose Villa. 1963. A Survey of the Literature of the Filipinos based on the Findings and Readings of Jose Villa Panganiban and Consuelo Torres Panganiban. San Juan, Rizal: Limbagang Pilipino.

- Parayno, Salud. 1991. Children’s Literature. Quezon City: Katha Publishing Company.

- Postma, Antoon, SVD. 1972. Treasure of a Minority. Manila: Arnoldus Press.

- Puedan, Al. 1988. “The Folk Literature of Antique.” Master’s thesis, University of the Philippines.

- Reilly, Brandon Joseph. 2013. “Collecting the People: Textualizing Epics in Philippine History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

- Reyes, Soledad. 2009. “The Komiks and Retelling the Lore of the Folk.” Philippine Studies 57 (Third Quarter): 389-417.

- Rizal, Jose. 1962. Rizal’s Prose. Manila: Jose Rizal National Centennial Commission.

- Roces, Alfredo R., ed. 1977-1978. Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation. 10 vols. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing.

- Tolentino, Delfin, ed. 2001. “Cordillera Literature.” In Filipinos Writing: Philippine Literature from the Regions, ed. Bienvenido Lumbera, 1-50. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

- Unabia, Carmen. 1996. Tula at Kuwento ng Katutubong Bukidnon. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Villanueva, Rene O. 2005. The Rene O. Villanueva Children’s Reader. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing.

- Villareal, Corazon, ed. and trans. 1997. Siday: Mga Tulang Bayan ng Panay at Negros. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Wein, Clemens, ed. 1989. Berinareu: The Religious Epic of the Tirurais. Manila: Divine Word Publications.

- This article is from the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Digital Edition. Title: Indigenous Traditions and Transformations in Philippine Literature Author/s: Florentino Hornedo / Updated by Laurence Marvin Castill URL: https://epa.culturalcenter.gov.ph/9/72/1537/ Publication Date: November 18, 2020.

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?